Author Wade Morris provides a detailed, nearly 200-year account of how the measurable academic report card has worked throughout history, says reviewer Stori Cox. She calls it "a fascinating read for those interested in understanding the why behind the hierarchy in education."

January 19, 2026

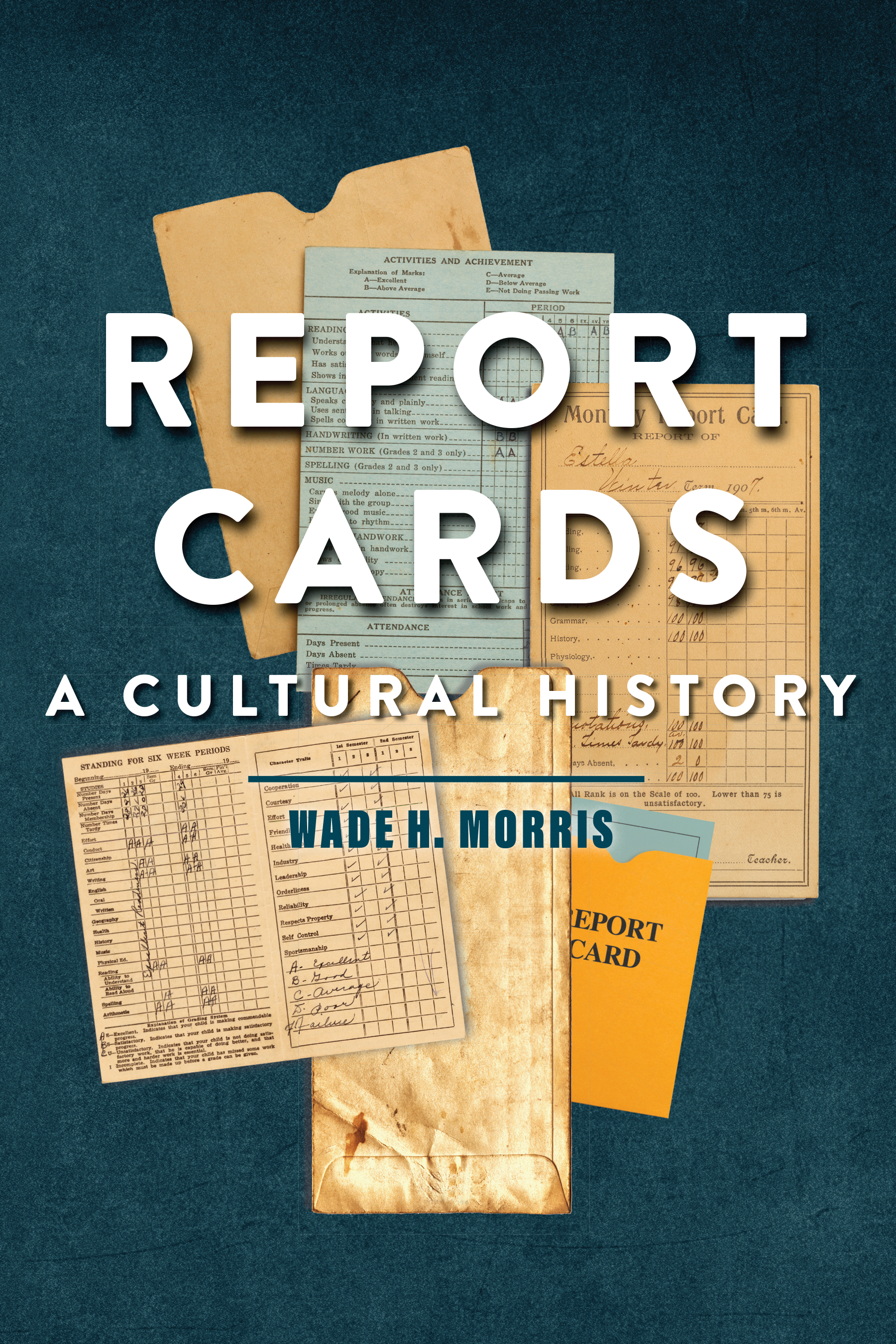

PHOTO COURTESY OF JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS

PHOTO COURTESY OF JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS

Report Cards: A Cultural History (Johns Hopkins University Press) offers a detailed account of how the measurable academic report card has worked throughout history. In the introduction, author Wade H. Morris shares that the idea for the book came as he prepared to flee Lebanon at the start of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. He had been in Beirut, Lebanon’s capital city, to visit a school archive and conduct research on the lives of classroom teachers during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990).

Underscoring the cultural importance of report cards, Morris learned that in 1982, during one of the war’s most intense periods, the neighborhood surrounding the school fell under siege; medical supplies, food, and clean water were all scarce. Civilians fled as best they could. However, he writes, “Before fleeing like many other West Beirutis, a handful of teachers and administrators met on campus between bombings to calculate and record grades on report cards.” And parents, “while also waiting for breaks in the bombing, came back to the campus to collect their children’s reports, sometimes delaying their flights from the siege to do so.”

This background, along with extensive research across the U.S., establishes Morris’ perspective that the history of the report card and all education evaluations should be studied as they have persisted through both war and pandemics. Morris, who earned a doctorate in education from Georgia State University, currently teaches history at United World College, East Africa, an international high school in Moshi, Tanzania, near Mount Kilimanjaro.

While unpacking how report cards operate as a method of communication between teachers and parents, the book had me questioning, “Do parents fully understand what teachers are assessing?” As a high school teacher myself, I found the text refreshing. Report Cards provides a historical perspective on some of the current issues in K-12 institutions. Grades are more than completing a task. They should be comprehensive evaluations of material after periods of practice. Students should never be graded on material during their first attempt at learning.

This is a common misconception among students and parents in the current educational era. If they do not understand the evaluation process for grading and report cards, teachers lose their ability to apply their expertise effectively. This disconnect between teachers and parents, a gap that has existed since the mid-1800s, will likely continue, Morris suggests.

The format of this book reflects on various protagonists of academia throughout time, providing a nearly two-hundred-year evolution of the report card, along with how parents, teachers, administrators, and students have responded to this evaluative documentation. Report Cards is a fascinating read for those interested in understanding the why behind the hierarchy in education.

Stori Cox (scox49@charlotte.edu) is a doctoral student at The University of North Carolina at Charlotte.