Recent Greenville County Schools graduate Nicholas Morales made history when he became the first South Carolina high school student to earn an American Welding Society pipe welding certification. His welding teacher at Greenville’s Donaldson Career Center, Wanda Haynes, says the certification has opened up a rare opportunity for him: a job offer from a Georgia nuclear plant. “That’s unheard of, because you usually have to have 10 years’ experience before you even go into the nuclear industry,” she says.

Although Morales’ parents worry that the job might derail his college plans, he says he still plans to attend. He came to the center in 11th grade from his home high school to see what welding entailed. “And then as soon as I got here, I realized it was a completely different world and the industry’s huge,” he says. “I just fell in love with learning about it.”

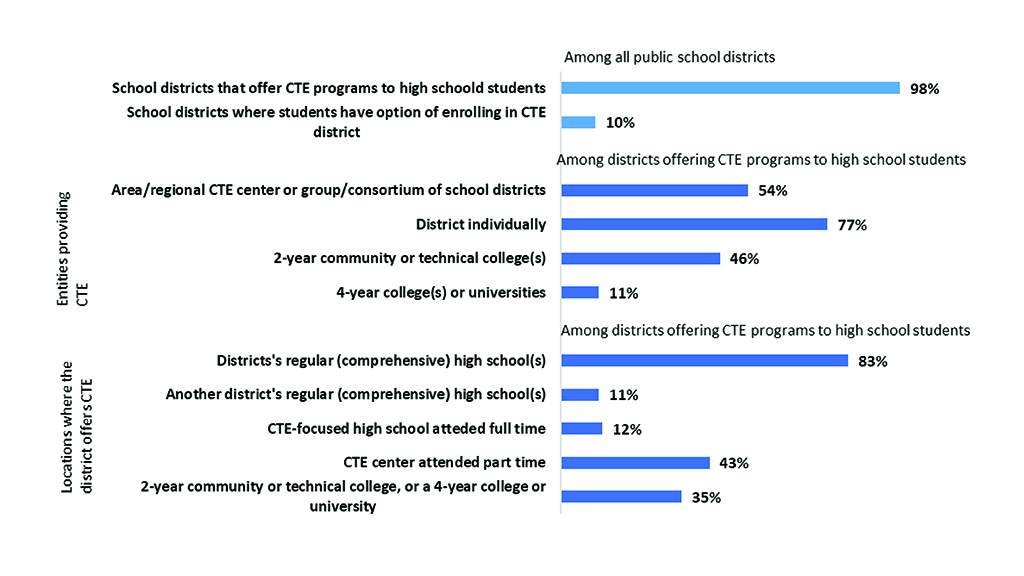

CTE by the numbers:

About 600 miles north, outside of Cleveland, Polaris Career Center student and high school senior Emma Whipple is also looking to her future. She attends the cosmetology program at Polaris and plans to get her license when she graduates. But she’s not stopping there. She’s going to a four-year college to become a cosmetic chemist and start her own cosmetics line. She’ll make money cutting hair and doing manicures while she’s at college.

Her classes at Polaris, she says, bring the academics and the career skills together, “the mainstream schools and the stuff I’ve learned here to formulate certain products that we can use in the salon.”

Share this content