While legislators are busy working out the pandemic relief plans on Capitol Hill, schools and districts are struggling to pass budgets for the 2020-21 school year. Just like COVID-19, there are many unprecedented uncertain factors affecting the ability of school leaders to make sound decisions. Enrollment changes and federal COVID relief funds have short- and long-term impact on K-12 school operations.

A Year of Uncertainty

The Bourbonnais Elementary District 53 in Illinois enrolled 2,554 students in 2018-19, of whom 45% were from low-income families and 18% were students with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). When the school board approved the district’s Fiscal Year 2021 budget in September 2020, the chief school business official said, “This was a very difficult budget, probably the hardest that I’ve worked on. With COVID, there are so many unknowns, … there are so many things that come about that we never thought would happen.”

The Lee School District in Florida enrolled 95,616 students in 2019-20; more than 71% of the district student population were poor. A vast majority of students (63%) were non-white, including 44% Hispanic and 14% Black. When the school board approved a $1.9 billion budget and $15 million for COVID-related purchases in September, the district’s chief financial officer said, “That dollar amount we have budgeted at this point is a conservative dollar amount. We tried to plan for what could be all of our students here all year long, and we know that’s kind of not where we are right now.”

How Enrollment Changes Affect School Funding

“Losing children means losing funding.” While this common saying may not always be the case, enrollment patterns play a big role in school district operations as well as statewide education policy. This fall, many districts experienced a decline in student enrollment due to the challenges created by the COVID pandemic, as some parents chose homeschooling, some students enrolled in private learning centers, and some students moved out of the district with their families.

Regardless of what the reasons are, student enrollment changes affect school budgeting. Some states do not provide per-pupil funding for students who have chosen homeschooling because of the pandemic. For instance, Grand Forks School District in North Dakota is facing the loss of state support, in per-pupil funding, for 78 students who elected to be home-schooled this year. Although the district exercises some oversight for students whose parents or guardians are responsible for their children’s education, the state does not provide per-pupil funding for the students.

In some states, student enrollment is tied to school funding, based on a formula that is used to allocate the amount of funding per student. For example, Port Angeles School District in Washington state dropped approximately 7% in its full-time equivalent student enrollment, which became a factor in a budget gap of more than $2.5 million. Due to the pandemic, not all students are full time (e.g., in Florida, Full-time equivalent (FTE) students are the basis for calculating the uniform funding system for public schools; one FTE is equal to 900 hours or 180 days of instruction, the equivalent of one regular school year). Therefore, a district may not receive the full funding per student as previous years. On the other hand, different programs may have different funding calculations, such as more dollars for career and technical education enrollees and an additional stipend for special education students.

Enrollment changes related to COVID-19 also create uncertainty for school operations in the long-run. In some districts, a substantial number of kindergarteners did not show up at the beginning of this school year. Parents might be waiting to enroll their children until schools resume in-person classes completely. It is unknown whether students who left public school for private or homeschool this fall did so temporarily or on a permanent basis.

Districts often trim their budget when they lose students. Cutting programs and laying off educators may reduce the budget deficit for the time being, but with the worsening situation of teacher shortages, the shrinkage of programs and staff will seriously affect the post-pandemic capability of public schools to serve students from low-income and disadvantaged backgrounds.

- According to the New York State teacher retirement system, there has been a 20% jump in retirements just during summer 2020.

- In Arizona, more than 1,700 teacher positions remained unfilled as of Aug. 31, 2020. In other words, roughly 28% of the classrooms in the state may lack teachers.

- With surges of educators filing for retirement or taking leaves of absence, school districts in Kentucky and many other states are even experiencing a shortage of substitute teachers. According to a recent report, some states, such as Missouri, Iowa, and Connecticut, have relaxed requirements to be a substitute teacher in preparation for a shortage of substitutes.

How the COVID Dollars Affect School Funding

Enrollment decline due to the pandemic has become a big concern for public schools, particularly those serving students from low-income families. Adding to this concern is the deadline of some COVID-related funding, which further complicated the school budgeting process. According to the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, states receive funds on the same proportion that each state receives under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) Title I-A, and distribute at least 90% of the funds to help schools, particularly high-poverty districts.

Districts acknowledged that the funds are helpful in covering costs that are not part of their normal budget, but the federal CARES Act funding expires on December 31, 2020. The deadline presents another unknown for school budgeting. In many states, such as Alabama and North Dakota, the health and wellness grants are only provided for the first semester of the 2020-21 school year, but some schools need to use the money to hire nurses for the whole school year.

While emergency federal funding is making its way to districts to offset budget cuts, it has not all been distributed. It is also unclear whether some of those unspent COVID-related dollars could be carried over to the next year. If not, it will put school administrators in a difficult situation – use it or lose it. Taking advantage of the COVID relief money is reasonable, but the juxtaposition sometimes leads to shortsighted policymaking and prolonged inequitable school funding issues.

- The financial help is intended for schools to purchase remote learning technology and equipment for sanitizing school buildings. When a district wanted to use CARES funds for ventilation improvement in the school buildings to prevent the virus from spreading, the answer was that the funds “are limited to salaries and contracted services beyond what we would normally incur” and cannot be used for equipment or building structural improvements.

- Without being given a chance to test the technology, a district that serves about 10,200 students across 13 campuses spent more than $178,000 on 52 walk-through infrared temperature scanners. Now, epidemiologists caution that mass temperature screening systems do little to detect people infected with the coronavirus and that they could make people less safe by giving the false impression that Covid-19 is not present.

- Although the COVID dollars help schools to accelerate digitalization, there have been supply chain challenges for districts to get the devices that students need. In New Jersey, about 193,000 schoolchildren needed computers or internet access for remote learning as of August 2020. The devices had been ordered as of mid-August, but there were supply chain issues that prevented devices from being delivered more rapidly. In Alabama, supply chain challenges increased the difficulty for districts to budget, as the state rule is that school districts must certify that they’ll spend the money before the state board gives the money to the district.

How Enrollment Projection Data Help School Leaders to Plan for the Future

The 2020-21 school year began with unprecedented uncertainty. In mid-August, 40% of parents of K-12 students across the US were reported to disenroll their children from the school they were originally supposed to attend this year in response to school reopening plans, according to a recent survey. With this unpredicted situation and the new approach to school operation under the COVID-19 guidelines of the Center for Disease Control and Intervention (CDC), schools are challenged to change both short term and long term. Data about student enrollment, school revenues, and per pupil expenditures become a must for district planning.

1. Disentangle the effects of the COVID-19 crisis on enrollment decline from larger trends that state education systems were seeing prior to the pandemic

School budgeting is always based on projected student enrollment, although this year districts face more unknowns. Since 1964, the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) has been publishing annual reports on projections of education statistics, including national data on K-12 student enrollment. The reports are intended to provide researchers, policy analysts, and school leaders with state-level projections developed using a consistent methodology. Assumptions regarding the population and the economy are the key factors underlying the projections of education statistics.

Although NCES projections do not reflect changes in national, state, or local education policies that may affect education statistics, student enrollment decline has become a trend. In 2018, NCES projected enrollment declines by 2026 in 19 states, 10 of which should expect declines of 5% or more. Most of these states are in the Northeast and Midwest.

Some of these regional losses are associated with the growth in homeschooling or school choice, but the more likely factors are family migration patterns, fertility rates, and regional economic opportunity. It should be noted that even in states where overall public K-12 populations are growing, not all districts are seeing new students. Therefore, school leaders should exercise caution when using the projected statistics. There are several limitations in the projection of NCES.

- Neither the actual numbers nor the projections of public and private elementary and secondary school enrollment include homeschooled students.

- The grade progression rate method was used to project school enrollments. This method assumes that future trends in factors affecting enrollments will be consistent with past patterns. It implicitly includes the net effect of factors such as dropouts, deaths, non-promotion, transfers to and from public schools, and state-level migration.

- The projections do not assume changes in policies or attitudes that may affect enrollment levels. For example, they do not account for changing state and local policies on prekindergarten (preK) and kindergarten programs. Continued expansion of these programs could lead to higher enrollments at the elementary school level.

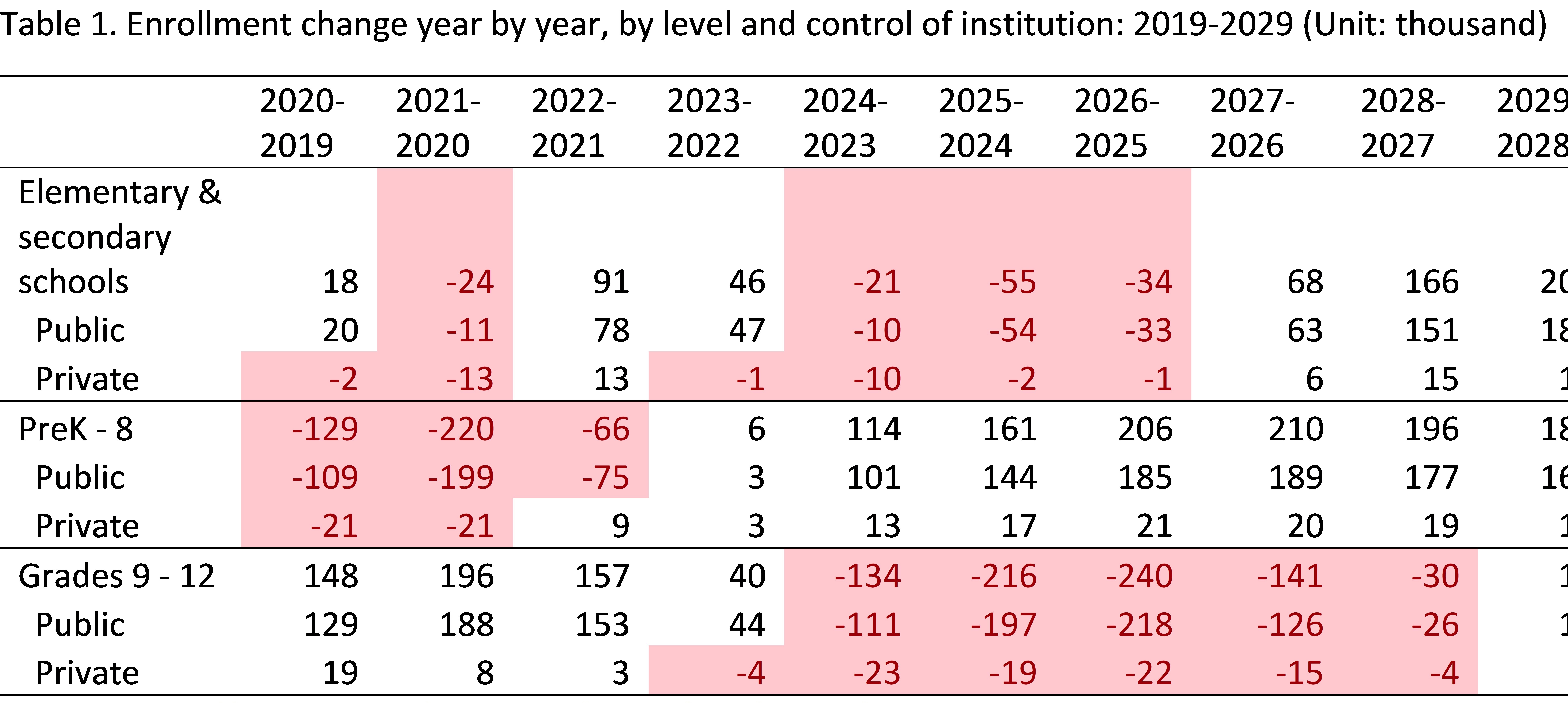

Despite the above limitations, school leaders should not ignore some projected national enrollment trends from 2019 to 2029. Compared with 2020, public elementary and secondary schools might see a decrease of 11,000 students nationwide in 2021, but an increase of 78,000 students right after in 2022 (Table 1). The projected data also show that PreK-Grade 8 enrollment would keep dipping between 2019 and 2022; in 2021, public schools were anticipated to lose 220,000 students in PreK to grade 8 from the previous year. By contrast, the drop of enrollment in grades 9-12 might come later and take place consecutively from 2023 to 2028.

Source: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_105.20.asp

Using the projected information, school leaders may ask themselves whether they are ready for the ups and downs of what may come. School districts may consider preparing a rainy-day fund, keeping a balanced budget in light of reduced enrollment and increased staffing costs, and getting as creative as possible with funding to cut minimally and reallocate their funds maximally to make sure their staff stay on.

2. Connect the dots between enrollment trends, per pupil expenditure, and revenue changes due to the pandemic

Student enrollment change matters. According to the ESEA, as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), Title I funds are allocated at the district level in all states, plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, based on mathematical formulas involving the number of children eligible for Title I support and the state per pupil cost of education. States receive the CARES funds also based on the same proportion that each state receives under Title I of ESEA.

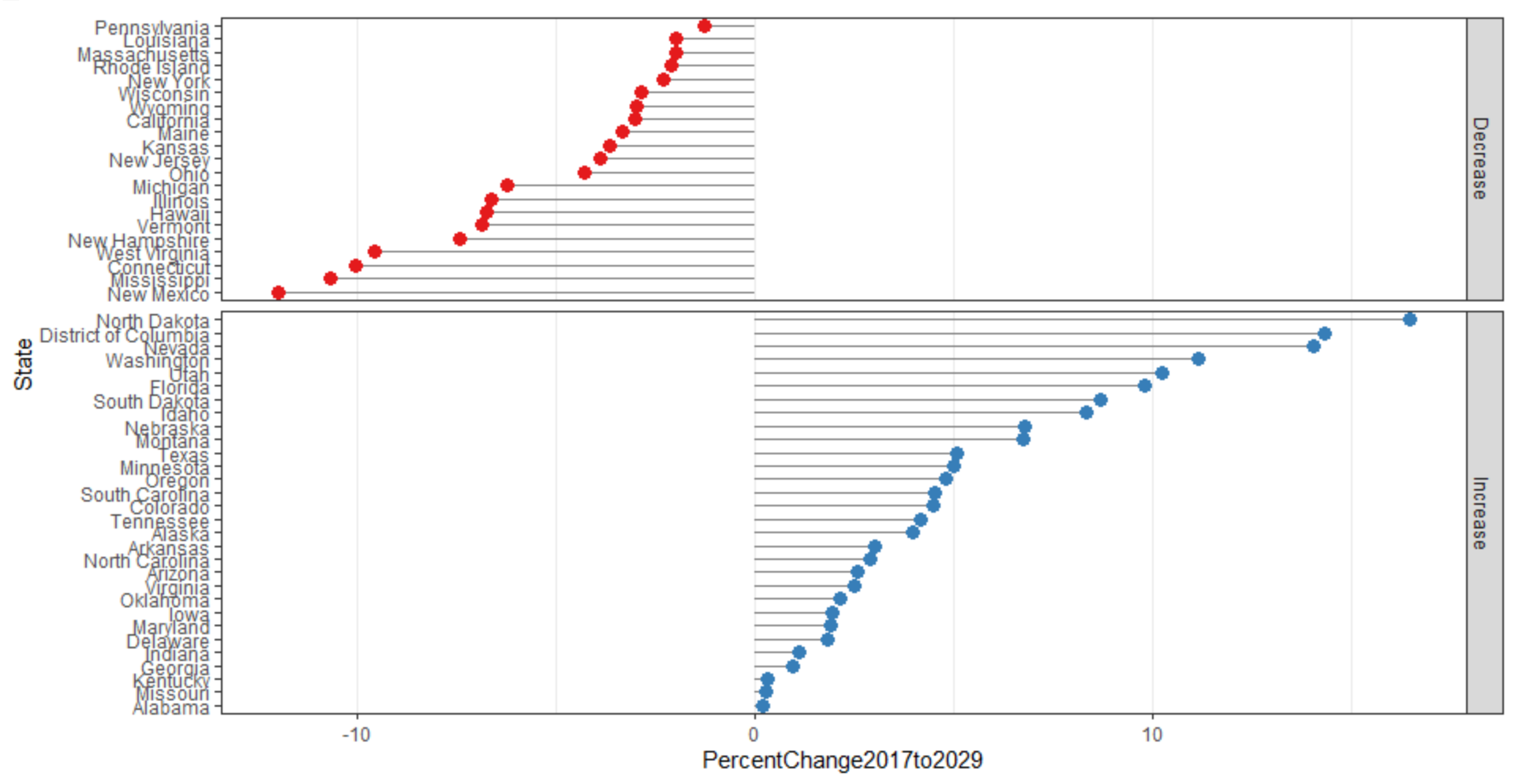

Logically, changes in student enrollment affect the allocation of both Title I funds and the distribution of COVID dollars, and have long-term impact on school budgets at district level. Figure 1 shows that between 2017 and 2029, 21 states (41% of the U.S.) are projected to see enrollment decrease. New Mexico, Mississippi, Connecticut, and West Virginia might experience about 10% or higher decline in student enrollment. In contrast, five states - North Dakota, District of Columbia, Nevada, Washington, and Utah – are anticipated to see at least 10% more new students.

Figure 1. Percent change in total enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools, by state: 2017 to 2029

Source: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_203.20.asp

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, school revenues are decreasing whereas costs are increasing. Some schools finished the 2019-20 school year with balance or surplus that came from savings on transportation and electric bills, but for the 2020-21 school year, many school boards across the country must face the predictable deficit in school budgets. Schools that had deficits in the previous fiscal year are more likely to be in deeper debt. On top of it, enrollment changes will aggravate the situation.

Michigan is one of the states projected to see an enrollment drop in the next decade. According to the Education Law Center (8/25/2020), Michigan approved a state aid cut of $175 per pupil in every district, totaling $256 million. The state then added $512 from the federal Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF), providing $350 per pupil to every district, along with $351 million through the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund under the CARES Act. Michigan’s combination of aid cuts and allocation of federal funding treated all districts the same, without regard to need, thus continuing the state’s longstanding pattern of “flat” school funding. Simply put, the coronavirus pandemic adds more pain to high-poverty school districts experiencing enrollment decline.

3. Think deeper about school finance and school transformation

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended the way schools are operating, the FutureEd's editorial director stated recently. Capital budget can include student technology; federal grants may cover internet hot spots; food funds support the mobile feeding program. However, some districts may still have to bridge a funding gap tied to lower enrollment by cutting staffing levels and introducing furloughs.

As these district leaders could not have possibly planned for an enrollment shock of this magnitude created by the pandemic, they have valid reasons to ask policymakers for additional support so they can stabilize their budgets, deliver virtual instruction, and protect the health of staff and students. Yet, beyond strong advocacy for public education, school leaders should rethink innovation and increase competitivity through school transformation.

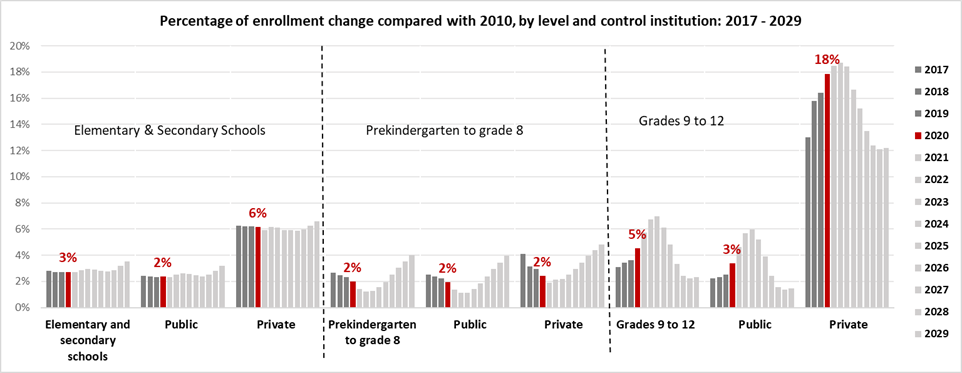

While 90% of K-12 students attend public schools, the projected enrollment data show that public schools may face a challenge in the next decade. That is the competition from private sectors (Figure 2). Using the 2010 enrollment as a benchmark, the increase rate of enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools is projected around 2%, whereas the index of private schools is as high as 6%. Compared with the 2010 enrollment in grades 9 to 12, the increase rate of private schools seems much higher than that of public schools. This trend is projected to persist all the way through 2029.

Figure 2. Percentage of annual enrollment change compared with 2010: 2017-2029

Source: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_105.20.asp

In summary, heading into a school year marked by uncertainty and increased responsibility, school leaders must make the most of federal funding that’s been allocated to help them forge ahead during a pandemic. At the same time, school leaders should increase awareness of projected enrollment data and seek a clear direction moving forward in school finance and school transformation.

Share this content