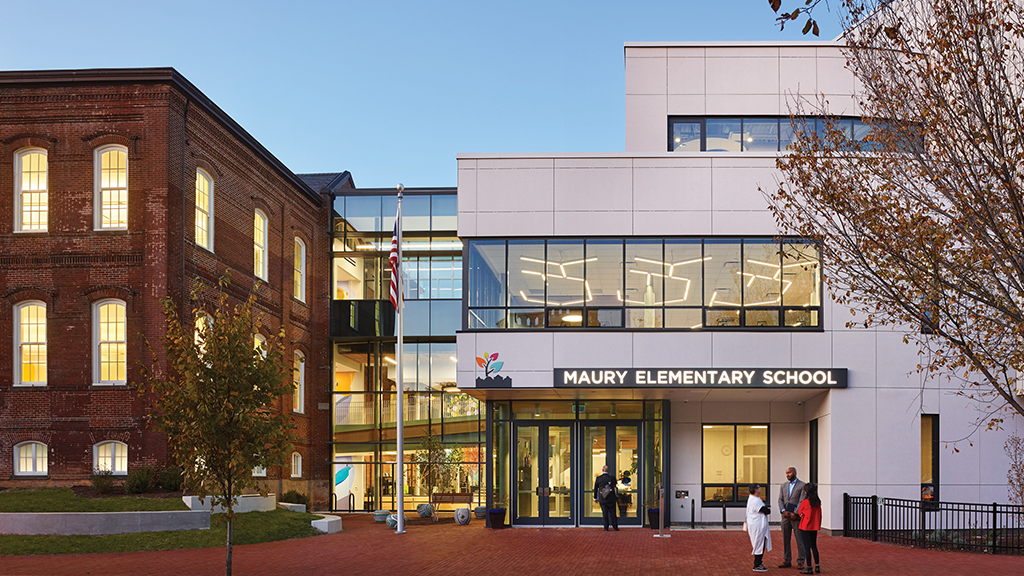

DLR Group’s renovation and modernization of District of Columbia Public Schools’ Maury Elementary School was completed in 2019. The design project connected new components with a historic building originally constructed in 1886. Photo credit: ©Alan Karchmer, courtesy of DLR Group

A school building boom is underway in central Florida. Over the past decade, Orange County Public Schools, the nation’s ninth-largest district, has built, replaced, or renovated 102 schools, more than half of its 202 schools, to the tune of $2.75 billion.

Long-range construction plans include four new high schools, four new middle schools, one new K-8, and 10 new elementary schools to open in the next 10 years to relieve crowding in high growth areas. Two of the “relief” high schools—Lake Buena Vista and Horizon—and one new relief elementary school—Village Park—open their doors in August.

District officials credit a half-penny sales tax that voters approved in 2003 and extended in 2014, plus residential development impact fees, for financing construction efforts. Along the way, they have learned a thing or two about effectively and efficiently renovating, modernizing, and replacing schools.

For starters, community engagement and detailed planning are essential, says Senior Construction Director Craig Jackson. “The earlier you can start planning things, the better. The more thorough you can plan things, the better.”

That advice bears repeating as the need for increased K-12 infrastructure investments receives critical new attention:

- The Biden administration’s American Jobs Plan infrastructure proposal called for $100 billion ($50 billion in grants and $50 billion in bonds) to modernize high-poverty schools with new school construction and upgrades to existing buildings.

- In Congress, the Reopen and Rebuild America’s School Act (H.R. 604 and S. 96) would authorize at least $100 billion in direct grants to schools, prioritizing those in underserved communities with the greatest need, and provide at least $30 billion in bond authority to states and communities.

“Providing a federal investment to repair, renovate, and construct school facilities that will be conducive environments for 21st century skills and learning is a huge win for everyone,” says Deborah Rigsby, NSBA’s director of federal legislation. “Many school facilities serve multiple purposes—for classroom instruction, professional development, career and technical education, and job training, health care, social services, public safety, community engagement, and more.”

Providing resources to communities that otherwise would not be able to finance capital improvements for educational services, like the massive undertaking in Orange County, “is a matter of equity,” Rigsby says. Those resources will “help ensure that all students have the supports they need to succeed.”

D+ for infrastructure

A 2020 report by the Government Accountability Office found that 54 percent of the country’s school districts need repairs to update or replace multiple building systems like heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) or plumbing. An estimated 41 percent of districts nationwide needed HVAC system updates in at least half of their schools to ensure proper ventilation.

That’s not surprising given that the average school building is roughly 44 years old, according to the most recent estimate by the National Center for Education Statistics. The “2016 State of Our Schools” report by the Center for Green Schools, the National Council on School Facilities, and the 21st Century School Fund calculated that state and local governments spend $46 billion less per year than what is required to update and maintain their school facilities.

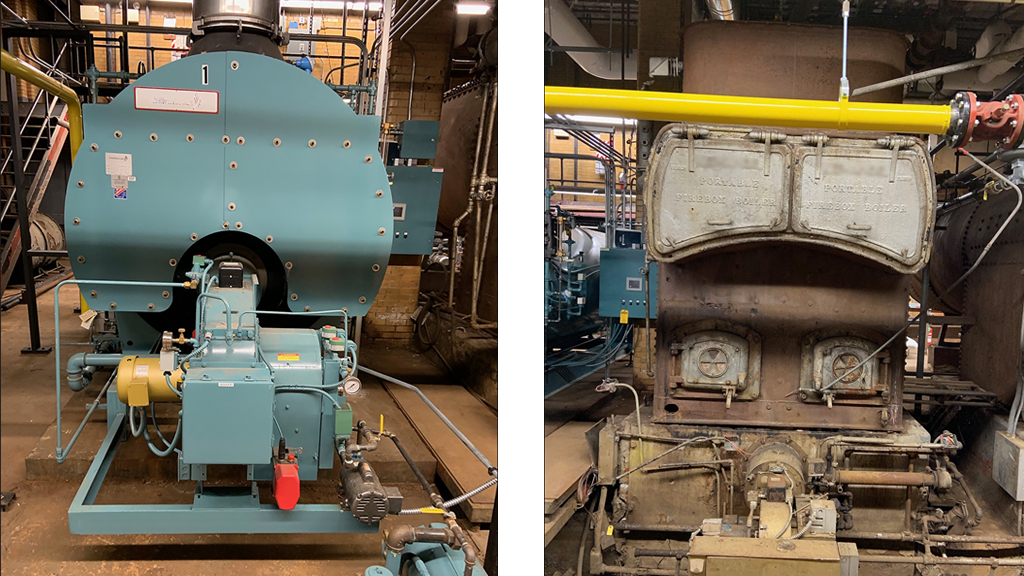

From the Government Accountability Office report, a public school in Rhode Island replaced a boiler original to the 1931 building (right) with a new boiler (left).

The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) gives the nation’s schools an overall grade of D+ for infrastructure. It says that four in 10 public schools do not have a long-term facility plan to address operations and maintenance. It notes that school facilities represent the second largest sector of public infrastructure spending, after highways, yet there is no comprehensive national data source on K-12 public school infrastructure.

Prioritize needs

Key to the work underway now in Orange County Schools was a comprehensive facilities condition assessment in 2013 of the district’s then 212 facilities to support the sales tax extension. It identified the life expectancy and replacement costs of roofing, mechanical, electrical, plumbing, HVAC, and other building systems. That information was crucial to establishing a “strong vision” for the district’s building plan, Jackson says. “If you don’t have that vision, things can be left out or left behind.”

Regardless of size or budget, every district needs an up-to-date school facilities evaluation, advises Charles Saylors, immediate past president of the South Carolina School Boards Association and a trustee for the School District of Greenville County. A longtime construction company executive, Saylors also is on the board of directors for the nonprofit Association for Learning Environments (A4LE). That assessment “should rank a district’s needs from most urgent to least,” he says.

Not only will it help district leaders prioritize the work ahead, an accurate evaluation also can be valuable when applying for federal or state funding that specifies shovel-ready projects. “It will give funders and the public an idea of where your needs are,” Saylors says.

School board members need to thoroughly acquaint themselves with the findings from the detailed assessment, agrees Mary Filardo, executive director of the 21st Century School Fund, a nonprofit that works to eliminate structural inequities in public school facilities. “They are going to have to make some tough choices, but they should make the choices with good information and do it with their communities.”

In conjunction with the National Council on School Facilities, Filardo recommends that every district develop and maintain a series of facilities plans, including:

- An educational facilities master plan to identify where schools are needed, if appropriate boundaries are in place, and if priorities for modernization or replacement are correct.

- A capital improvement plan to help implement the master plan by documenting approved uses for capital funds, setting priorities, and defining the scope of projects (i.e., location, timing, and financing) over a multiyear period to ensure equity and affordability.

- An ongoing operational and maintenance plan to focus on schedules and budgets for routine and critical maintenance of buildings and grounds. For example, are the dampers open on air handling units? Are air filters being changed regularly? Do the filters accurately fit?

“There are not a lot of shortcuts or simple fixes to buildings that have had deferred maintenance,” Filardo says.

Keep in mind that for all the excitement around potential new school facilities funding opportunities, “any influx of federal funding is a temporary situation,” cautions Eric Schnurer, a veteran public policy advisor at the state and federal level. “There needs to be a lot of future thought about what are the life cycle costs of the investments you’re making and where are you going to get funding long term to support an upfront investment now,” he says. Schnurer directs Elevated Solutions, a member service of NSBA. Its independent team of former superintendents, principals, educational services specialists, and government efficiency experts review districts’ operational practices to find cost-saving opportunities that allow districts to function more efficiently and effectively.

Keep the learning environment in mind

To help determine demand and capacity for Orange County School’s buildings, the district pays attention to demographics, enrollment patterns, relocation trends, and land-use data, Jackson says. Those areas may not fall under construction or facilities, “but they play into the planning process.”

Accurate, reliable forecasting is challenging but essential, says JoAnn Cox, a district operations consultant with Elevated Solutions. “If that’s not in place, all of the other tasks are null and void.” Today, however, gathering that data is even more difficult as school districts attempt to meet parents and students’ demands for distance learning, brick-and-mortar learning, and hybrid learning.

When looking at infrastructure improvements, architect and former school system facilities administrator John Chadwick encourages districts, if possible, to “really raise the systems in their buildings” instead of simply replacing “like equipment with more efficient like equipment.”

He points to unit ventilators under the windows of many older schools that are often “challenged to provide the amount of air changes or fresh air that’s required. The newer ones are OK but are often very noisy,” Chadwick says. A principal with integrated design firm DLR Group, Chadwick was previously the assistant superintendent of facilities and operations for Virginia’s Arlington County Public Schools.

Acoustics are a huge issue in classrooms that directly impact students’ ability to learn, he says. “We were in a school recently where the HVAC had just been replaced, and students could barely hear. You really want school systems to think about the learning environment, not just the HVAC or air quality on its own.”

Construction of the auditorium at Orange County Public Schools’ new Horizon High. The Florida high school opens in August.

Though attention to the importance of air quality in schools ramped up exponentially because of the pandemic, so have questions about some high-tech air cleaning systems that claim to fight COVID-19. Specifically, bipolar ionizers and ozone generators have come under scrutiny. In May, a class action lawsuit was filed against a top-selling ionizer technology “claiming that its devices don’t work as advertised and that they could emit harmful chemicals,” NBC News reported.

In April, an open letter signed by a dozen prominent scientists, engineers, and consultants in the field of indoor air quality urged school districts to “recognize the unproven nature of many electronic air cleaning devices.” It added: “As they are unproven, it is critical to avoid wasting valuable emergency COVID relief aid dollars installing them within school district facilities.”

There are “proven technologies that help clean the air” that are “backed by quality science,” says Michael Garceau, general manager, building management systems North America for Honeywell. “We tend to advocate those.” Ultraviolet light and MERV-13 or better air filters “are tried-and-true technologies that have been used for years and years.”

In addition to cleaning the air, well-maintained HVAC systems are essential to improving energy efficiency, says Garceau. “That’s one of the main reasons why districts want to improve their HVAC systems.” But one size does not fit all, he adds. “You have to look at your facility, your goals for the facility and the challenges. Do a physical audit of how the building operates and what equipment you have, then work up a solution. It’s easy to skip that step and throw a Band-Aid on.”

Design features

As schools look at opportunities to improve their buildings’ infrastructure, they also can consider renewable and sustainable energy solutions to lower their carbon footprint, consume less energy, and provide long-term savings, says Chadwick. While at Arlington Public Schools, he oversaw the design and construction in 2015 of the first school in the nation to be LEED Zero Energy certified by the U.S. Green Building Council.

According to the school system, the design of Discovery Elementary results in $117,000 of annual utility cost savings compared to a typical elementary school in the district of the same size. The school’s interactive energy dashboard, adjustable solar panels, and other “green” features support an array of experiential learning programs.

To help districts support energy efficiency, ABM Industries’ energy performance contracting is designed to convert wasted energy and utility inefficiencies into funding for facilities and other programs. Like the company’s noninstructional spend analysis program, the goal is to help districts “improve their spend pattern” by highlighting strategies to lower excess costs, says Dan Dowell, ABM senior vice president.

Design features inside school buildings that reflect current and future innovations in education also should be considered as districts look at new infrastructure work. Learning in the classroom no longer demands 30 or more desks lined up in straight rows. Instead, classrooms need to be agile, with a variety of spaces for various learning activities. Even furniture that can be easily rearranged helps support the concept that “every space becomes a learning space,” Chadwick says.

Access to natural light, green spaces, and outdoor learning areas, along with appropriate heating, cooling, ventilation, and acoustics, “are all in support of a more inquiry-based and activity-based learning model,” says architect Jana Silsby, a principal and design team leader with DLR Group.

Among the innovative features of Agua Fria Union High School District’s Canyon View High School in Waddell, Arizona, is a variety of flexible spaces that can change throughout the day depending on the specific small, medium, or large group activity scheduled. Teaching and learning spaces are more reflective of the educational spaces evolving in business and industry. Photo credit: ©Tom Reich, courtesy of DLR Group

STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) education programs benefit from a classroom model that’s more flexible, larger, and has more storage, Cox says. “Too often, facilities and infrastructures are built, and then the academic programs have to fit the infrastructure. It should be the other way around,” she says.

Transparency and accessibility

Transparency within schools and into schools is another feature that Silsby and her design colleagues favor. Students seeing what’s going on in other classrooms and teachers seeing what’s happening in other parts of the building are stimulating and lead to more significant interaction and collaboration, Silsby says. Transparency also lowers opportunities for bullying, she adds.

Some may perceive a conflict with security and transparency, Chadwick says. “We’ve had several of our facilities evaluated by Homeland Security, and one school in particular with a great deal of transparency inside had the highest rating” for security. One likely explanation: “You have more eyes on what’s going on,” he says.

Making schools accessible and engaging for students “with all levels of ability and disability as seamlessly as possible” should be another key design goal, Chadwick recommends. Often, schools will have steps at the entrance and ramps on the side for students, staff, and visitors who use walkers or wheelchairs, have mobility difficulties, or are pushing strollers. That design inadvertently separates people by ability.

A more inviting option, he says, is a design where everyone uses the ramp, eliminating that separation. “It’s an example of design through a lens that makes school as accessible as possible for everyone. To us, that’s very exciting.”

In Orange County Schools, construction director Jackson says he particularly appreciates creating facilities that support the district’s extensive range of learning programs, be they STEM, culinary arts, or special education. “I’m proud to be a part of that and constructing these facilities that have all of these up-to-date ideas and visions. We know how important it is for our students.”

Share this content